Called liposomal amphotericin, it packages the active ingredient within tiny droplets of fat that are infused into the body intravenously, for hours a day, over a week.Īll three men had a rough time. Yoder, Fisher, and Preston were able to start with a slightly safer compound. Several can damage the kidneys and require a long course of treatment. “The therapies are usually toxic and not very friendly,” he admitted-and the explorers found that was true. Nash confirmed that Yoder had leishmaniasis.įive members of the expedition agreed to go to NIH to be treated by Nash. Yoder wangled an introduction to Theodore Nash, who is a principal investigator in NIH’s Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases. After some exploring on the Web, he thought he had identified the cause.

He had contacted several others, and they had the same thing. Then Dave Yoder got in touch: He too had a lesion that was not healing. And buggy: The constant rain washed away the strongest insect repellents, and the explorers were tormented by chiggers and dive-bombed by mosquitoes.Įven given the revelatory finds-evidence of walls, buildings, and plazas, and a cache of sculpted objects-the group was relieved to emerge from the jungle and head home. It was drenching wet under the layers of foliage, and chilly. In a ten-hour day, you might be lucky to go three miles.” “Some of the densest jungle in the world. “Forty-five-degree slopes, and roaring torrents in the ravines,” said Douglas Preston, a best-selling author who recounted the trip for National Geographic magazine along with photographer Dave Yoder. When the remote imaging revealed structures that might add up to two cities, a team of more than 40 people-including geologists, anthropologists, ethnobotanists, and a camera crew, all guarded by Honduran military-struck out into the jungle. Steve Elkins and Bill Benenson, two documentary filmmakers obsessed by old accounts that Honduras’s remote Mosquitia region concealed a lost “white city,” recruited him to interpret images taken above the forest canopy. He used it a few years ago to reveal that a pre-Columbian site in central Mexico was far larger than explorers on the ground had detected. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates there may be more than one million cases a year, caused by different subspecies of the parasite.įisher is an expert in the imagery produced by lidar, a technology that deploys laser pulses to look through vegetation to the concealed ground beneath. Leishmaniasis is barely known in North America but very common in Central and South America and the Middle East. “I’m not Indiana Jones,” Chris Fisher, an archaeologist at Colorado State University and a National Geographic grantee, said ruefully. The team members have returned to their homes, and most of them have recovered-but the episode has been an unexpected reminder of the dangers that can dog even the best-prepared fieldwork. medical institutions that research the disease and regularly treat patients.

#PARASITE CITY TION SKIN#

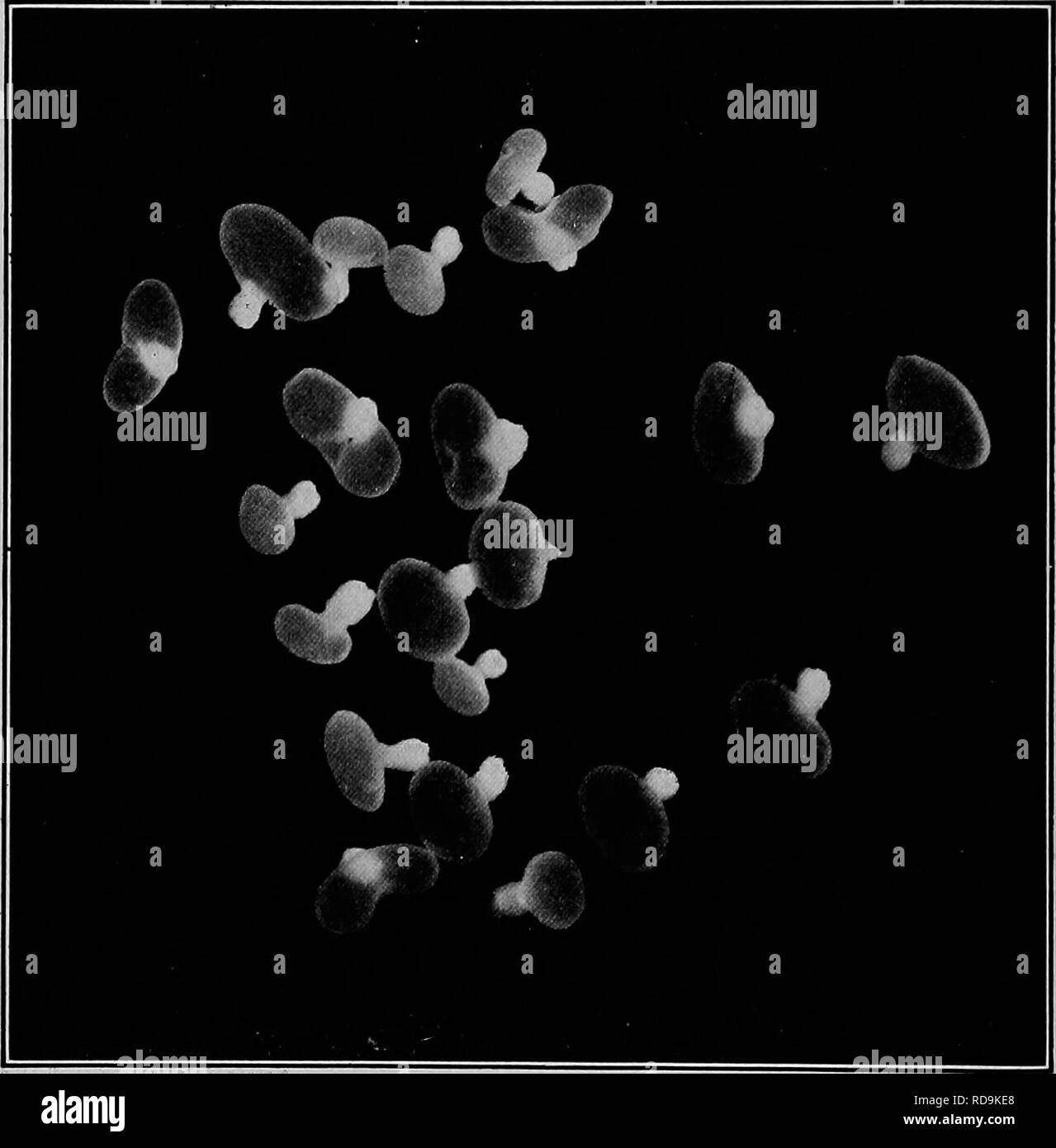

The illness was transmitted by sand flies that swarmed the explorers in stinging clouds.Ībout half the people on the expedition, described in the October issue of National Geographic, have been diagnosed with the illness, which is caused by parasites that break down the skin and can cause weeping, potentially disfiguring sores.įive were so ill that they were sent for treatment at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health, one of the few U.S. Members of a successful recent expedition to find a lost city in the Honduran rain forest have returned to the United States with an unwelcome souvenir: infections from the tropical disease leishmaniasis.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)